Global Shield Briefing (3 July 2025)

Emerging risk, tipping points and the new nuclear age.

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

A country’s power – its ability to shape the world around it in line with its interests – is so often measured in military might, economic heft and cultural clout. But if that power fuels the rise of global catastrophic risk, what is it really worth? And if a smaller country can avert that risk, should it not be considered powerful in its own right? This edition is about the leadership role that small and middle-sized countries can play. They often hold more power than they know. While geopolitical giants grapple with gridlock and rivalry, global catastrophic risk grows. The so-called minnows, however, can become pioneers of prevention and architects of resilience. Whether preparing for climate tipping points, pressing for a world without nuclear weapons, or navigating emerging risk, these countries remind us that influence isn’t always about size. True power is measured by what gets accomplished.

Simplifying complex risk

![Firefighters are extinguishing a plane fire at the 'Ready Korea' training held at Incheon International Airport on the 5th. The training was conducted on the assumption that the plane left the runway while landing and collided with a bus, causing a number of casualties. [Reporter Han Joo-hyung] Firefighters are extinguishing a plane fire at the 'Ready Korea' training held at Incheon International Airport on the 5th. The training was conducted on the assumption that the plane left the runway while landing and collided with a bus, causing a number of casualties. [Reporter Han Joo-hyung]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!qWgY!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffe0949a4-e063-4073-97a0-1eaf10ddc4af_700x239.jpeg)

The OECD has released a report on national risk governance systems and institutional capacity to address novel and complex threats. Based on the case studies of Ireland, Israel, South Korea, and the US, as well as the OECD’s emerging critical risk framework, the report makes several recommendations for governments, including: dedicated institutional roles for systematic risk identification; regular updates and iterative processes to respond to dynamic risk environments; cross-departmental and transboundary engagement for managing emerging risk; and advanced technologies and methodologies for enhanced risk identification and assessment.

Policy comment: The report provides a solid blueprint for government agencies to take more proactive measures to manage emerging risk. The key – and often missing – ingredient is political ownership. Unless heads of government and agencies buy into risk governance, the bureaucratic efforts to assess and manage risk will be lacklustre. In some cases, the lack of direction and ownership from senior levels is deliberate; formally and publicly assessing risk creates a public expectation that nationally significant risk is being addressed by the government, who fear they will suffer politically if they fail. On the other hand, clear ownership creates a positively reinforcing cycle. The UK’s Head of Resilience or Israel’s National Emergency Management Authority (two examples highlighted in the report) showcase how a specific individual or agency has been tasked with driving risk assessment and management. Or take Chief Risk Officers (CROs) in financial institutions. Replicating something like these CROs can build risk practice and culture across the government enterprise. They can help manage gaps and overlaps between agencies. And they provide a single point of coordination that their heads of state can turn to in a world of emerging and increasingly catastrophic risk.

Tipping away from catastrophe

The Global Tipping Point Conference convened over 30 June to 3 July. The first Global Tipping Point report in 2023 identified 26 tipping points in Earth’s climate and environmental systems, such as the runaway melting of Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the dying off of warm-water coral reefs, the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), and the thawing of permafrost regions.

Climate researcher and conference host, Timothy Lenton, states that tipping point risk has been underestimated: “When we did our first assessment in 2008, we thought Greenland was close to a big tipping point. We haven’t changed that judgment, but we thought West Antarctica would need at least 3C of warming [above pre-industrial levels]. Unfortunately, everything that’s been observed since suggests we were way too optimistic. As a rule, the more we learn, the closer we think the tipping points are – and meanwhile we’ve been warming the planet up.”

The Global Tipping Points Report 2025 is being developed ahead of COP30 in Brazil. Contributions to the report can be made via tippingpoints@exeter.ac.uk.

Policy comment: Climate tipping points represent a unique need of global catastrophic risk – the need for both prevention at the global level and preparedness at the national level. To slow the rate of warming to under 2 degrees celsius, which might be critical for many of the tipping points, major powers, like the US, China and the EU, need to collaborate. However, countries, particularly smaller ones, cannot wait. For example, the collapse of the AMOC could reduce food, water and energy security for billions of people in Africa, Europe and Asia due to drastic changes in regional rainfall and temperatures. Half the area for growing staple crops worldwide could be lost. The potential for tipping points are an opportunity for governments to stress-test their supply of food, water and energy. Efforts to improve national preparedness and resilience would help protect against tipping points as well as other global catastrophic threats. Countries could look to invest in crops more tolerant to naturally occurring hazards, develop national food reserves, strengthen supply chain resilience, and support local food production to reduce dependence on vulnerable imports. Similar, for water security, countries could look to build water storage and recycling systems and strengthen mechanisms for water allocation and rationing in emergencies. To the extent that countries are conducting national risk assessments, tipping points of all types might need special attention due to their growing likelihood and escalatory cascades once they tip.

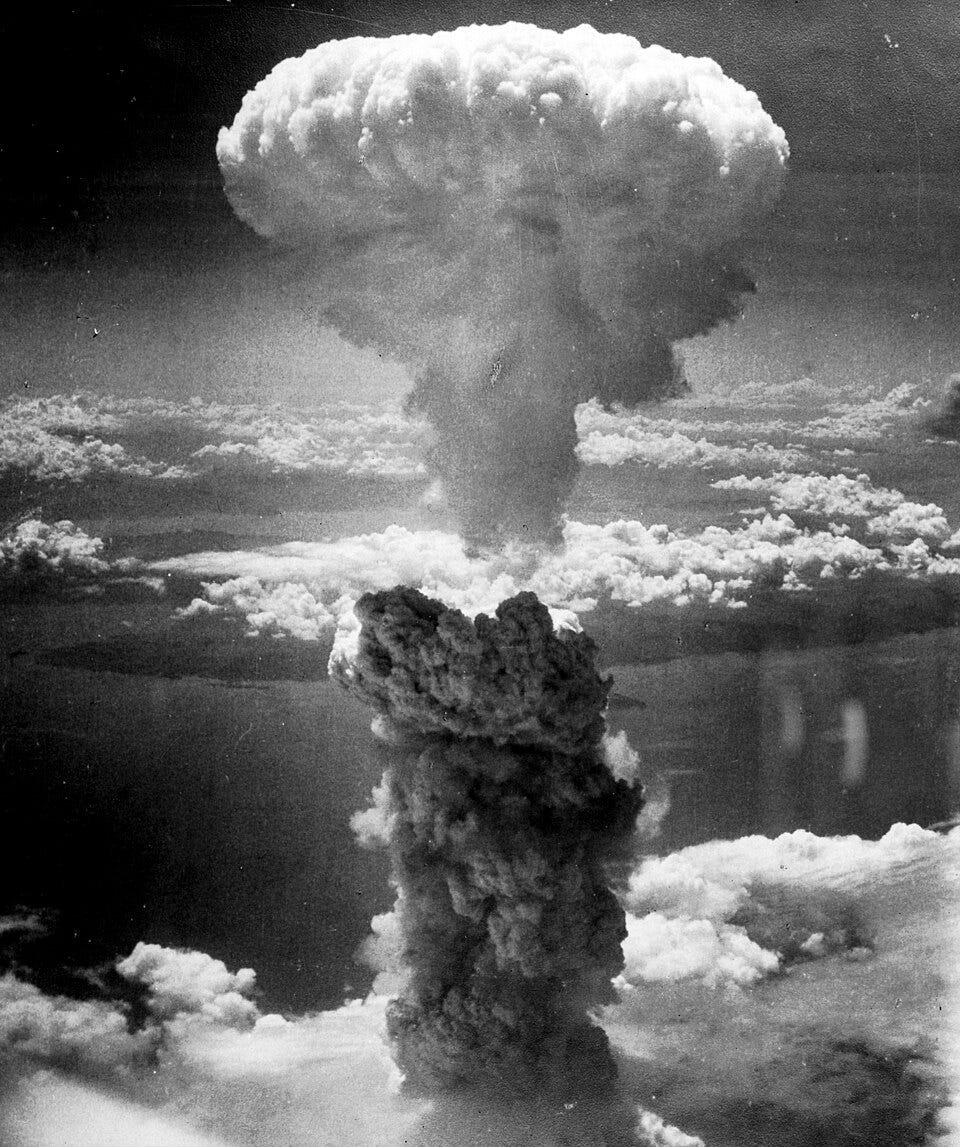

Reversing the growing nuclear risk

Just as the world marked the 80th Remembrance of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, two recent conflagrations – the India–Pakistan conflict in May and the recent conflict between Israel, Iran and the US – has brought nuclear risk back to global attention. Iran’s powerful Guardian Council has approved the parliament’s bill to suspend cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). It would align Iran somewhat with India, Pakistan and Israel, who are not parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Meanwhile, the UK’s new defence review sees it adding about $20bn to its nuclear forces, including the deployment of air-launched tactical nuclear weapons through the purchase of 12 F-35A jets from the US.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine has published a report, as directed by Congress, that re-examines the potential environmental, social and economic effects of a nuclear war. The recommendations mostly focused on further research that the US government could conduct, including suggesting that the “Departments of Health and Human Services, Defense, Energy, and Agriculture should collaborate in the development and implementation of an enterprise-wide approach to assess the potential societal and economic impacts of a nuclear detonation on food, water, and health.” While the study did not include modeling, a group of researchers are investigating food and fertilizer trade disruptions on global food security in the context of nuclear winter.

The Washington Post is examining the “next nuclear age” in a series, highlighting the increased risk and complexities of the global nuclear landscape compared to the Cold War. The series, a collaboration with the Federation of American Scientists, explores how nuclear weapons proliferation and modernization efforts pose new challenges for international security. One piece looks at the overall global nuclear landscape. Another looks at the US president’s sole authority for launching nuclear weapons. A third looks at the reasons some countries are contemplating starting their own nuclear weapons programs. A fourth goes into the ways a nuclear war could start, especially by accident.

Policy comment: Nuclear risk continues to grow. Nuclear-armed states are investing more in their nuclear weapons programs, just as multilateral and bilateral treaties are being degraded. On the current trajectory, it seems unlikely that the nine nuclear-armed states can or will work together to reduce risk, and recent trends might give other states greater incentive to pursue their own programs. As a result, middle powers, smaller countries, and civil society organizations must apply renewed pressure. In multilateral forums, they might have a better shot at championing these efforts because it is less likely to be viewed through a geopolitical lens between major powers. During the Cold War, for example, landmark weapons treaties – such as the Arms Trade Treaty, the Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel landmines, and the convention banning cluster munitions – were pushed successfully by middle powers and advocacy groups in the face of veto-holding Security Council members who produced and used such weapons. UN resolution A/C.1/79/L.41 (“Steps to building a common roadmap towards a world without nuclear weapons”) approved by the General Assembly in December 2024 presents the foundations of just an effort. Advocacy could focus on key sponsors of the resolution, especially Japan, as the driving force behind it, and other drafters with strong ties to nuclear-weapon states, such as Australia, Canada, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia and Sweden.

Also see:

A new book, “Six Minutes to Winter: Nuclear War and How to Avoid It” by Mark Lynas.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, an international advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.