Global Shield Briefing (27 August 2025)

A national resilience strategy, AI preparedness and climate tail risk

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

“Be alert but not alarmed.”

It’s what Australians were told in 2002 to warn them about the threat of terrorism. There was a large-scale media blitz, led by the prime minister. A dedicated hotline was set up – its number helpfully displayed on fridge magnets. And every household received a booklet detailing what to do in the event of an attack.

But the phrase transcends that context; it is now more relevant than ever. A simple slogan for a complex time. A pithy reminder of the dangers we face, from the local to the global, from the mildly inconvenient to the utterly catastrophic. A call for a shared commitment to safety and security.

More than that, it must be a trigger for action, not just for the everyday citizen, but all the way up to the highest office. For with alertness comes duty. To move past passive vigilance – towards preparedness, planning, and resilience, before the alarm bells toll.

Some, it seems, are ahead of others.

Crafting a national resilience strategy

The UK Government has published its “Resilience Action Plan”. It notes that “we cannot perfectly predict how risks will unfold, and across all risks we need some common systems and tools to respond. For this reason, the UK government also works to improve the general resilience of the nation to all risks - the ‘all hazards’ approach.”

It includes dozens of important commitments and actions, including developing a Risk Vulnerability Tool for highly vulnerable people and groups, establishing a “red team” capability to assess the next National Capabilities Assessment, building a comprehensive resilience measurement, developing a new Cyber Resilience Index, conducting an annual public survey of risk perception and preparedness, investing in critical infrastructure resilience, improving public communication about the national risk register and national preparedness, and conducting a review of the Civil Contingencies Act.

It reaffirms the actions it has taken for catastrophic risk, including stronger governance in the Cabinet office, clear thresholds and triggers for responding to catastrophic emergencies, and mapping key cascading impacts of catastrophic risk.

In conjunction with the resilience plan, the UK Government has released its first analysis of chronic risk. In contrast to the acute threats and hazards typically covered by the national risk register, this chronic risk analysis covers the long-term challenges that threaten the country and exacerbate the likelihood or consequences of acute risk. The types of risk covered in this report include those with catastrophic potential, including climate change, biodiversity loss, animal disease, artificial intelligence, and bioengineering.

Policy comment: The UK’s national resilience plan is an example many other countries can follow. In contrast to national security strategies, strategic defense documentation, and disaster risk or resilience frameworks, a national resilience strategy takes an all-hazards approach for the full range of risks and threats facing the nation. It could then integrate global catastrophic risk to ensure that uncertain, long-term, chronic or highly unlikely threats and hazards are captured. There are three main challenges to navigate for a national resilience strategy. First off, it needs to be in a broader context of national risk assessment and national preparedness. For example, the US is currently developing a national resilience strategy as part of a March 2025 Executive Order that directs a full-scale review across a range of federal policies for critical infrastructure, food system resilience, national continuity, preparedness, and response. The second challenge is a clear policy owner. For example, Denmark recently combined a range of resilience, civil defense, preparedness, and emergency management functions from across government under a single agency (“Ministeriet for Samfundssikkerhed og Beredskab” or “Ministry of Civil Security and Emergency Management”). Third, the strategy must consider how resilience would be affected, and probably overwhelmed, by global catastrophic risk. Testing the strategy under such extreme circumstances would ensure policymakers understand the point at which resilience could fail.

Building preparedness and readiness for AI risk

A new research report looks at the situations where advanced AI systems act in unintended, dangerous ways beyond human control, and explores measures to strengthen emergency management and preparedness strategies. It notes that “Future critical failures from advanced AI models could trigger widespread disruptions across essential services and infrastructure networks, potentially amplifying existing vulnerabilities in other domains. Developing comprehensive emergency response protocols could help mitigate these significant risks.”

Policy comment: AI could create new categories of risk (e.g., autonomous decision-making), exacerbate existing threats (e.g., biological hazards, cyberattacks, misinformation), or intensify vulnerabilities to other hazards (e.g., critical infrastructure, democratic resilience, water and energy insecurity). Ideally, governments take necessary preventative action to reduce AI risk. As with the automobile, societies will better make use of the technology once there are adequate technological safeguards (e.g., seatbelts, better brakes) and policy regulations (e.g., road standards, driving tests, traffic laws). However, in the current geopolitical and domestic political contexts, where safety is perceived to slow AI progress (a false dichotomy in our view), preventing AI-related harms in the first place is increasingly difficult. Proactively building preparedness and readiness is a potential failsafe to AI safety policy and technical efforts not preventing harms from occurring at the outset. Governments and societies that are preparing for AI risk, and disruption in general, will be less vulnerable to creeping AI risk as well as AI-driven incidents and crises. Preparedness would also reduce the costs and harms associated with AI-related failures. Three general areas that policymakers can focus are: monitoring and adapting to the potentially disruptive social, economic and security effects of AI; building situational awareness and threat detection for AI-related crises and incidents; and establishing plans and protocols for responding to AI-related crises and incidents.

Wagging the tail risk

Two pieces in The Economist cover climate tipping points, irreversible changes in regional or global ecosystems that could greatly disrupt the global climate. The collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), covered in one piece, could lead to relatively sudden changes in climate, particularly in the northern hemisphere, including vast areas of food production. The head of the UK-based Strategic Climate Risks Initiative told The Economist in the other piece that “no government is considering scenarios like ice-sheet collapse with the seriousness afforded to other high-impact risks” and that “most governments have not really been thinking about them at all.”

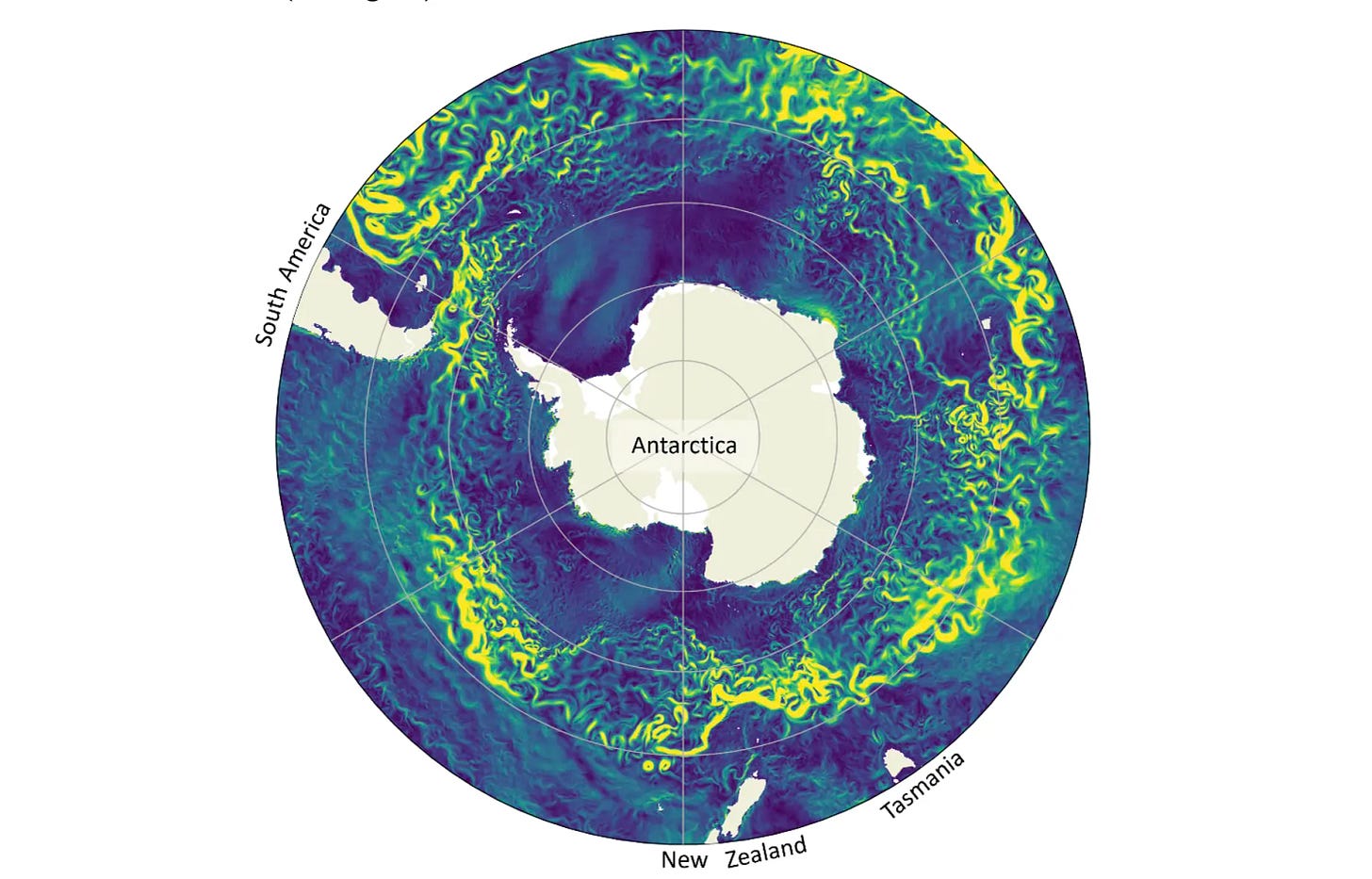

Two recent papers look at the impact of climate change on Antarctica, and the broader global implications. A recent Nature article assesses that “A marked slowdown in Antarctic Overturning Circulation is expected to intensify this century and may be faster than the anticipated Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation slowdown. The tipping point for unstoppable ice loss from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could be exceeded even under best-case CO2 emission reduction pathways, potentially initiating global tipping cascades.” A May research letter found that meltwater from Antarctica is speeding up the Antarctic Slope Current (the westward current flowing around the continent), which could accelerate meltwater loss.

Climate tipping points form only one “planetary boundary” – the safe operating space for critical Earth systems, like freshwater, land, and the biosphere. Another one of the nine planetary boundaries has crossed into the danger zone: “novel entities” such as pesticides, radioactive materials, and microplastics. A new investigation by Deep Science Ventures explores toxicity from chemicals and contaminants, and its impact on health and the environment. The report states that “toxicity appears to be a threat to the thriving of humans and nature of a similar order as climate change.”

Policy comment: The tail risk of climate change and environmental damage is high. Six of nine planetary boundaries have been crossed. Meanwhile, three of the nine climate tipping points are at their threshold, and two more will be more likely to tip at 2-4 degrees of warming. It is not clear exactly where Earth’s systems stand in relation to these thresholds. But the impacts could be non-linear and catastrophic – which goes against the common thinking that tail impacts are linear (a bit more emissions = a bit more risk) or manageable (adaptation and mitigation will be enough). If policy only plans for the most likely or median scenario, it systematically underestimates catastrophic risk. More research and investigation are required to reduce uncertainty and improve visibility of dangerous levels. Governments need to stress-test their national resilience against various scenarios of these critical Earth systems breaking down.

Hiring an Australia policy associate

Attention Aussies – Global Shield's newly established Australia office is growing!

We are seeking a dynamic and driven Associate or Senior Associate to help shape Australia's policy responses to the biggest threats of our time. Policy success in Australia on global catastrophic risk sets a standard many other countries can follow. Your work for Global Shield Australia will be world-leading.

The successful applicant will report to our Australia Director and work at the intersection of policy, advocacy and communications. Their work will include shaping and driving our Australia office’s strategy and engaging with senior policymakers, politicians, and the media to drive policy outcomes that reduce global catastrophic risk. This role provides significant potential for impact and professional growth.

If you have experience in a parliamentary office, government relations, journalism or media engagement, policy advocacy, or policy development, we strongly encourage you to apply.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, an international advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.