Global Shield Briefing (21 August 2024)

Dealing with catastrophic climate change and pandemic scenarios

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

The line between knowing and not knowing can be the difference between action and inaction. Whether in our individual lives or for policies that shape the trajectory of a nation, the better the information, the greater the confidence in taking the first step. For global risk, policymakers face a genuine quandary: how does one know what actions to take, or how much of it, for a highly uncertain future? Well, for the extreme risk of climate change or of another global pandemic, uncertainty is no refuge. The stakes are high, the experiences are fresh, the expertise is available and the actions are clear. The key to unlocking a proper effort on reducing global catastrophic risk is political will.

Understanding and preparing for worst-case climate scenarios

Benjamin L. Preston, a senior policy researcher at RAND, argues that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) should better consider global catastrophic risk in its next iteration of its report. Specifically, he suggests that “clarifying the emissions pathways under which catastrophic and existential risks are likely to occur would benefit negotiations around greenhouse gas mitigation as well as adaptation strategies that hedge against high-end risks.”

The World Climate Research Programme, an international effort that helps coordinate global climate research, has kicked off a stream of work to understand and identify risk from low-probability, high-impact events with global ramifications. They are hosting a workshop in November at the World Meteorological Organization in Geneva on the topic of high-risk cascading shocks.

In March, the Australian government released the first of two reports assessing climate security risk. It noted that “The very nature of risks means their impacts are uncertain but decision makers need to consider the most severe possible outcomes – a plausible worst case scenario. Such scenarios are integral for policy planning and decision-making to mitigate and adapt to such risks.” The second report, due to be released by the end of 2024, will cover the 11 areas prioritized as facing significant risk: defence and national security, infrastructure and built environment, health and social support, natural environment, primary industries and food, regional and remote communities, communities and settlements, governance, supply chains, water security, and the economic, trade and finance sector.

Policy comment: Policymakers must properly investigate the worst-case scenarios of climate change. It is a highly under-studied area of climate science, with climate researchers, including the IPCC, focused heavily on baseline scenarios. So the World Climate Research Programme effort on catastrophic climate risk is welcome. Funding or replicating its work would be an important first step. As their work shows, multidisciplinary experts and advanced modelling techniques are needed to better understand extreme scenarios where our knowledge is limited, such as large sudden natural carbon release, ice shelf collapse, massive shift in oceanic or atmospheric circulation, cloud feedback loops and biome collapse like in the Amazon. The specific policies to prevent climate change, like scaling renewable energy, might not differ dramatically between baselines scenarios and more extreme scenarios. However, studying these scenarios might change approaches to preparedness and resilience. Should extreme climate change scenarios present a greater risk than expected, policymakers could take measures that improve a country’s ability to withstand severe shocks. In particular, it would help inform policy measures to reduce the vulnerabilities that exacerbate climate change risk, such as social disunity, food and water insecurity, disinformation and misinformation, governance gaps and supply chain resilience.

Also see:

A new academic paper by the Executive Director of the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute that argues that climate change should be considered a global catastrophic risk, despite (indeed, because of) the uncertainties around potential scenarios and the impact of human interventions.

A post on the political and economic upheaval that is likely in the US over the next 15 years due to climate change, including the potential for a global food shock.

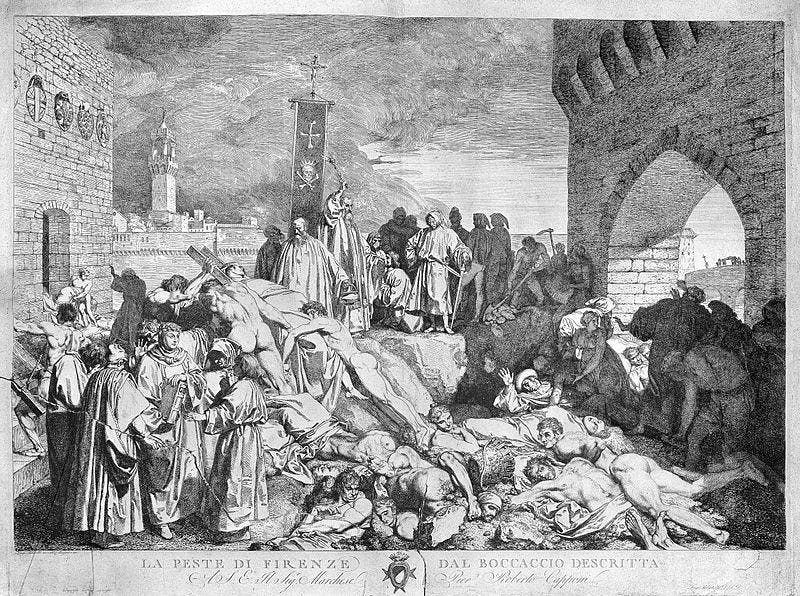

Preparing for the next inevitable pandemic

The Director-General of the World Health Organization has declared mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) after the surge of cases primarily in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), as well as up to 12 other countries in Africa. The Emergency Use Listing for mpox vaccines has been triggered, accelerating vaccine access and distribution, particularly for lower-income countries.

In June 2024, the World Health Organization updated its list of pathogens of pandemic potential. The list sits at 30, and includes influenza A virus, dengue virus and, ahead of the recent PHEIC announcement, mpox. In the report, they advocate for focusing on research of viral and bacterial families rather than isolated pathogens deemed to present global risk. As the report notes, “this strategy bolsters the capability to respond efficiently to unforeseen variants, emerging pathogens, zoonotic transmissions, and unknown threats such as ‘Pathogen X’.”

A new piece in Foreign Affairs notes that “governments and international organizations have done far too little to prepare for [another pandemic], despite the lessons they should have learned from the global battle with COVID-19.” They make a number of recommendations, including improving medical countermeasures like vaccines and diagnostics, improving the design and systems for manufacturing personal protective equipment, investing heavily in vaccine research and development, and adopting a military model of planning, procurement, and development for pandemic preparedness.

Control Risks, an global risk consultancy, assesses that “Climate change, urbanisation and deforestation combined with economic pressures and geopolitical tensions will sustain global vulnerability to infectious disease outbreaks, including another pandemic, in the coming years”.

Policy comment: As the previous briefing noted, very few countries have completed a detailed review of the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s increasingly clear that, despite recent experience, most countries will not be prepared for the next pandemic. Experts and health departments generally know what is required. But it is a lack of will and funding from senior policymakers that is the major roadblock. The only way countries can adequately prepare for global pandemics is for governments to have a mindset shift. Specifically, pandemic readiness must be treated with the same level of political will, urgency and indispensability as national defense. Around 2.3% of global GDP is spent on militaries, and many countries have an explicit 2% target. An equivalent measure is not even known for spending for pandemic preparedness and health security, though experts estimate it is a “small fraction” of defense spending. This discrepancy sits in stark contrast to the fact that conflict and pandemics both killed around 100-150 million people over the past century. Governments should normalize a target for pandemic risk reduction spending. Ending pandemics could be a national ‘moonshot’ for a head of government with the foresight and courage to protect their country.

Also see:

A 2021 report (that remains extant) by an expert panel on behalf of the G20 that provides concrete recommendations and specific figures for financing pandemic risk reduction efforts nationally and globally.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, the world’s first and only advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.