Global Shield Briefing (16 April 2024)

Using every tool in the policy toolkit to reduce global catastrophic risk

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

It feels natural to treat specific threats within their own domain. Environmental policy for climate change. Defense policy for nuclear weapons. Technical solutions for the risk from artificial intelligence. But global catastrophic risk requires using every tool in the policy toolkit, especially those outside the policy domain. As Albert Einstein apocryphally stated: “No worthy problem is ever solved within the plane of its original conception.” It means using economic and financial policy to grapple with climate change and other types of tail risk. It means smaller players – whether middle powers or advocacy groups – using their muscle to shape the risk that emanates from big companies and bigger countries. It means seeing that an AI catastrophe is one scenario within a wide technological risk profile. As you read through this briefing, consider all the policy tools at our disposal, and how tools for one threat can be elevated to global catastrophic risk in its entirety.

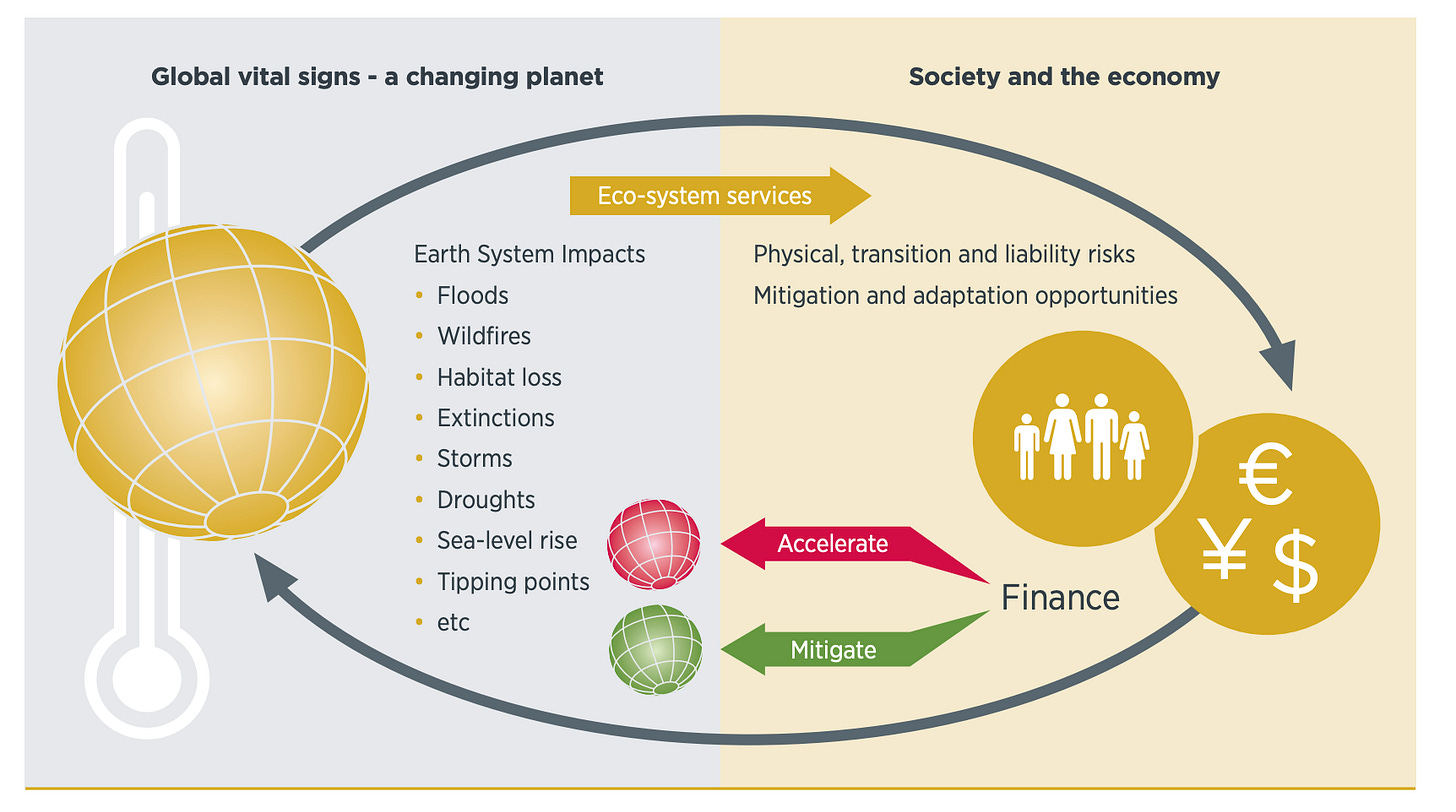

Recognizing the financial aspects of catastrophic risk

New research highlights the financial aspects and economic policy of climate change. A recent paper by Matthew Burgess offers five policy considerations for climate risk. These include the need to improve investment and incentives to reduce emissions, carbon capture to remove existing emissions, and adaptation for coping with the effects of climate change. Adaptation might be the most attractive to policymakers, because the effects are local and immediate, yet remain the most underfunded. Meanwhile, a new report by the Climate Bond Initiative finds that the sustainability-linked bond market remains relatively immature, with only 14% of loans over the past five years aligning with climate goals. Taking an actuarial lens to climate risk, the UK’s Institute and Faculty of Actuaries calculate the potential losses from extreme climate change. They conclude that “even without considering cascading impacts, there is a 5% chance of annual insured losses of over $200 billion in the next decade, with total (insured and uninsured) economic losses breaching the $1 trillion mark.”

Policy comment: Beyond just climate risk, the economic, financial and budgetary impacts of global catastrophic risk remains heavily overlooked. Advocates and policymakers should build tools that estimate the expected annualized impact of GCR. These tools can utilize methods already developed in insurance, bond and climate finance markets. The fiscal impact would be based on inputs such as emergency response, relief payments, recovery costs, tax and debt relief, insurance payouts and reduction of tax receipts. The economic impacts could include job losses, GDP contraction, market volatility and the second-order impacts from damage to healthcare, energy and agriculture sectors. A dedicated team within countries’ respective Treasury departments could lead this effort. As part of this work, they should estimate the expected annual economic impact of different catastrophic scenarios and perform cost-benefit analyses for various risk reduction efforts. The analysis could provide political and policy justification for critical preventative and preparedness activities.

Reducing risk as a smaller player

Major AI players are pushing forward on the development, regulation and coordination of AI applications and safety. On April 1, the US and UK governments announced a formal partnership on AI safety, in which the governments have committed to “align their scientific approaches and (work) closely to accelerate and rapidly iterate robust suites of evaluations for AI models, systems, and agents.” And in the coming weeks, official US-China dialogues on artificial intelligence will kick off, as agreed to by presidents Biden and Xi in November 2023. Like many pivotal moments in diplomacy, the road to this official engagement was paved slowly and quietly. For example, over the last 5 years the Brookings – Tsinghua University Track 2 dialogue has been convening experts from each country to discuss sensitive issues on AI. A similar dialogue, the International Dialogues on AI Safety (IDAIS), met in Beijing in March, where AI experts made a joint statement on the need to avert an AI-related catastrophe.

Most other countries, which have little ability to shape the trajectory of AI development, will have to decide how they intend to manage the opportunity and risk from AI. For example, in Australia, the Select Committee on Adopting Artificial Intelligence has been established to investigate the impact of AI on Australia’s society and economy. A report is due in September.

Policy comment: The majority of sources of global catastrophic risk, much like for AI risk, emanate from a small group of governments and companies. This phenomenon presents a challenge for policymakers outside of those jurisdictions. Their countries bear the consequences of the risk while having limited ability to shape it. However, middle powers and civil society organizations with global reach are not without impact or influence. For example, smaller countries and dedicated advocacy efforts were instrumental on arms control treaties in the 20th century, like for chemical weapons, biological weapons, small arms and light weapons, and landmines. These actors can play an important role by raising global catastrophic risk in multilateral and regional forums. Those forums that include the likes of the US, China and Russia are particularly important, such as the East Asia Summit, the UN Security Council and the G20. Partners of major powers could also help shape their thinking by conducting internal assessment of risk and advocating it through bilateral engagement.

Building holistic policy for technological risk

A new paper in Science by world-leading AI researchers highlights a type of AI system called a “long-term planning agent,” which the authors argue presents an underappreciated risk. Long-term planning agents are particularly difficult to test for safety and pose the most substantial threat because of their incentive to develop and execute plans on a longer time horizon than systems like image generators. A recent article for the European Leadership Network’s online publication looks at the potential terrorist use of large language models for chemical and biological weapons attacks. A report by the International Center for Future Generations looks at five emerging technologies – advanced artificial intelligence, neurotechnology, biotechnology, climate intervention, and quantum computing – that have transformative and world-changing potential. RAND has released the next report in a series on the effects of emerging technologies on homeland security, with this latest paper focused on AI and how it relates to critical infrastructure.

Policy comment: There is no one-size-fits-all policy to managing technological risk, nor should policymakers be playing whack-a-mole. Global catastrophic risk emanates from a range of different technologies, and the same technology can be harmful in different ways. Fixating on one particular scenario or threat vector creates blindspots to the various ways global catastrophic risk arises. Governments should approach technological risk more holistically. Governments could implement a systematic process to evaluate and categorize existing or emerging technologies based on their potential to pose catastrophic risk – similar to the process outlined in the RAND series. They would then need to continually refresh the risk assessments, re-evaluate impacts on critical infrastructure and national security, and engage in novel foresight and forecasting exercises to test assumptions and existing policies. This agile process could be the basis for targeted controls, oversight and regulations on high-risk technologies.