Global Shield Briefing (1 August 2025)

Risk interconnection, AI race dynamics and a letter to Congress

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

Risk can often be quite abstract. Instead, consider scenarios. In the UN Global Risk Report, covered in the first section, four scenarios are presented, with the “breakdown” scenario painting an eery, if familiar, vignette: “In an increasingly fragmented world, the multilateral system is under severe strain and unable to take joint action to prevent or prepare for global risk”. A new RAND report on AI geopolitics, covered in the second section, imagines eight scenarios, showing the wide array of futures, each plausible and challenging in their own right. Or take our new primer on the Defense Production Act and global catastrophic risk, covered in the third section, outlining two potential scenarios where mobilizing private industry would be critical to catastrophic crisis response.

Scenarios are not predictions. They are stories. They are a bridge between imagination and reality. They help us envision the unexplored territory in a dark forest, stretching us beyond what feels comfortable or obvious. But they ground those visions in tangible and realistic narratives. Scenarios, when done right, let us explore uncertainty in concrete terms. They let us turn abstract risk into actionable insights. They raise difficult questions about our readiness. Ultimately, scenarios of the future are a stress-test of the present.

Finding interconnections across the risk landscape

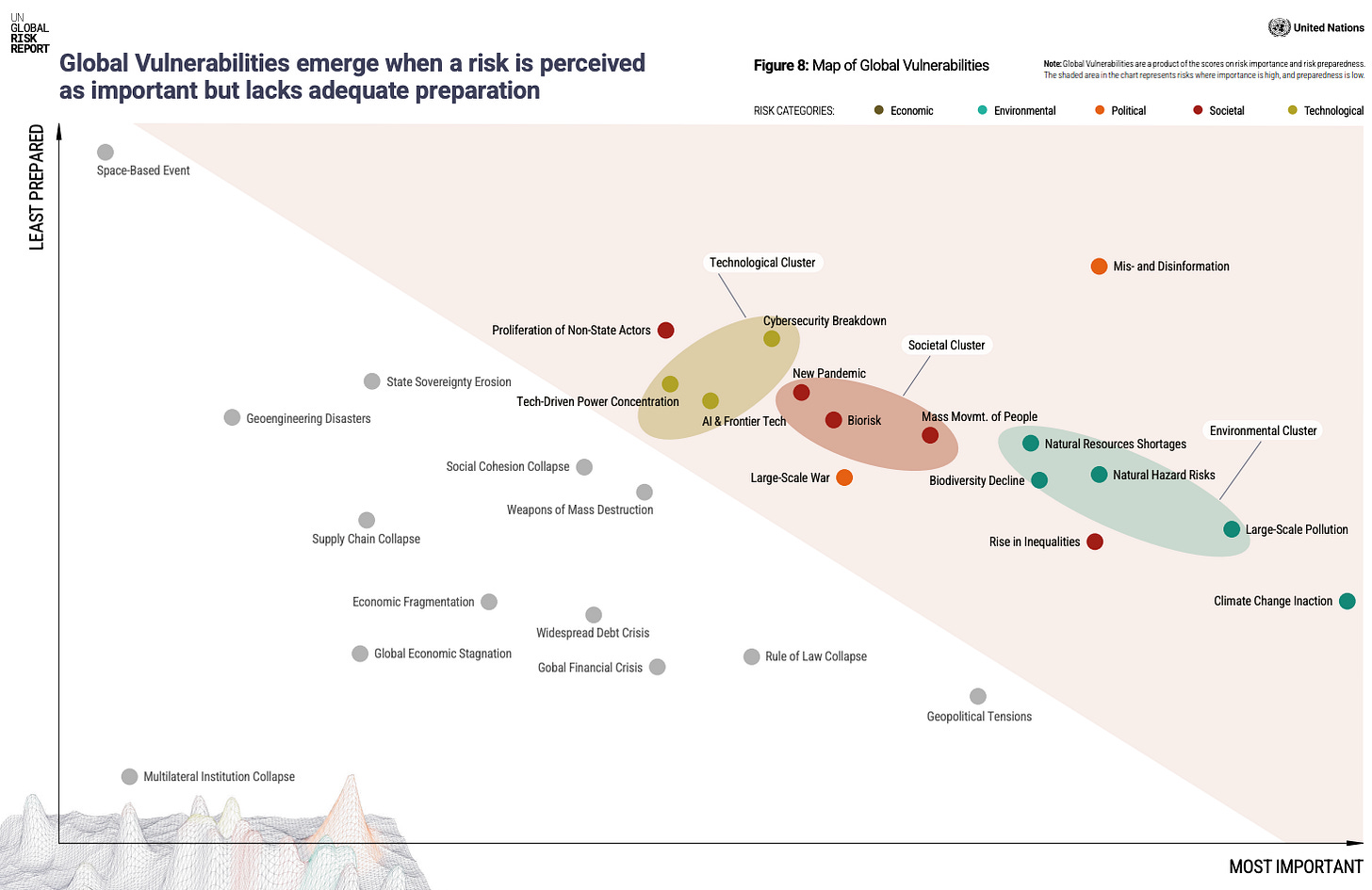

The UN Secretary General has released the inaugural UN Global Risk Report. Stemming from the UN’s Our Common Agenda, it is the first effort by the UN to consider threats and hazards of all kinds. The purpose of the report was to inform multilateral system’s work in managing global risk. In the study, 28 threats and hazards were assessed on likelihood, severity, imminence and interconnectedness by over 1,100 survey participants. According to the report, the multilateral system is most unable to deal with the global rise of mis- and dis-information. Further serious vulnerabilities fell into three primary clusters: environment (natural resources shortages, natural hazard risks, biodiversity decline, and large-scale pollution); technology (cybersecurity breakdown, tech-driven power concentration, and Al and frontier tech); and societal (mass movement of people, biorisks, and pandemics).

The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) has recently released its biennial Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction (GAR). The theme of this report was the growing cost of disasters and the opportunities for investing in disaster risk reduction. It found that, between 2001 and 2020, the direct costs of disasters averaged $180-200bn annually, an increase from $70-80bn a year between 1970 and 2000. Disaster costs now exceed over $2.3 trillion annually when cascading and ecosystem costs are taken into account. Meanwhile, around two percent of development aid is directed towards disaster risk reduction.

The UN University also published the 2025 Interconnected Disaster Risks report. It outlines five key changes to achieve a desirable future: realigning with nature, rethinking waste and resource use, reconsidering our responsibilities towards other people and communities, reimagining the future and their opportunities, and redefining value.

The Global Governance Forum published its 2025/2026 Global Catastrophic Risk Index in April, an update of the inaugural index in 2022. It provides an assessment of global vulnerabilities and resilience across 163 countries. The most at-risk countries are assessed to be Yemen, Afghanistan, Haiti, South Sudan, and Sudan; the least-at-risk countries are Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, and Iceland. The report states that “that risks cannot be considered distinct and must be understood as interconnected, interdependent, and compounding.”

Policy comment: The common theme emerging from these global risk reports is interconnectedness. The various challenges we face are interconnected; crises bleed over borders; the boundaries between human and technology are almost indistinguishable. And as the UN report makes clear, the management of 21st-century risk will “require holistic and systemic responses,” especially because efforts to solve one problem might make another worse. This means that global risk must be dealt with at a more fundamental and comprehensive level. Traditional risk management practices, like risk assessment, preparedness and resilience, and crisis response, can form the foundation of this management. However, it might not be enough in reducing risk overall. It might require new forms of governance, changes to economic models, transformative approaches to food and energy production, and community-building at the local level. As the UN University report states, “instead of treating problems as separate, isolated events, we can take interconnectivity as the starting point and build our systems from there.”

Tempering AI race dynamics

The White House has released its AI Action Plan. The plan, and the reporting around it, have highlighted the race dynamics, mostly with China; indeed, the action plan is titled “Winning the Race”. Despite the heavy focus on promoting a domestic AI industry and leading globally on AI, one of the plan’s three pillars is risk and safety: “we must prevent our advanced technologies from being misused or stolen by malicious actors as well as monitor for emerging and unforeseen risks from AI.”

Earlier in July, RAND published a report on the potential impacts of the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI) on geopolitics and the world order. It paints eight different scenarios based on the degree of decentralization of AI development and the degree that AGI empowers the US on an absolute and relative basis. It notes that “U.S.-China technological competition features prominently across the scenarios. The dynamic between these powers—whether characterized by cooperation, competition, or conflict—shapes the trajectory of AGI development and deployment.”

An article on the AI race between the US and China by a Biden-era National Security Council official states that: “Policymakers around the world are ill prepared to manage these combined strategic and technological developments. Many struggle to stay up to date with AI developments, let alone plan for the geopolitical ramifications of new breakthroughs. But they must prepare now to mitigate these risks. The coming years will be far more dangerous than many of the technology’s investors and policymakers realise.”

Policy comment: Framing AI development as a race can undermine efforts to manage the risk that both governments recognize to be in their mutual interest to reduce. A race mentality can further speed up risky development of the technology by disincentiving safety measures that are perceived to slow innovation of capabilities, and can reduce transparency and trust between companies and the countries. Under race conditions, the possibility of severe public and economic backlash to the job displacement effects of advanced AI might be more damaging to long-term strategic aims of the racing powers involved. Despite this framing, particularly by the media and by AI companies, there is more agreement between countries on AI risk than meets the eye. In July, for example, Canada hosted the third directors-level meeting of the International Network of AI Safety Institutes, including a joint testing exercise across nine countries. Governments should work individually and together to understand, prepare for and manage the transition to transformative AI, even under perceived race conditions.

Reauthorizing and modernizing the Defense Production Act

Global Shield organized a letter alongside a diverse set of other organizations urging Congress to reauthorize and modernize the Defense Production Act (DPA) of 1950, which expires on 30 September 2025. The organizations represent a diverse set of civil society groups and US domestic industries that are essential to the US’ national and economic security, including in the critical minerals and pharmaceutical manufacturing industries. The signatories urge Congress to 1) Reauthorize the DPA for a minimum of six years this calendar year, thereby avoiding the inefficiencies and uncertainty of short-term clean reauthorizations; 2) Consider bipartisan modernization to better align the DPA with 21st-century threats and supply chain realities, such as the FORCE Act (H.R. 3561) and the CLEAR Act (H.R. 3542); and 3) Support robust annual appropriations for the DPA Fund, which enables targeted, strategic support to domestic industries critical for national defense.

Policy comment: Over the past 70 years, the DPA’s authorities have become the foundation of US preparedness for and response to national emergencies arising from all threats, with a wide range of uses. Throughout the Cold War, the DPA enabled domestic industries to out-compete the Soviet Union in the provision of military equipment. The DPA’s definition of “national defense” explicitly encompasses domestic emergency response due to amendments to the Act. So, when major natural disasters have occurred, the DPA has helped communities get priority access to the critical materials they need to support response and recovery operations. Should a global catastrophe occur, the government would also need support from private industry, and the DPA will be central to that effort.

See a primer on how the DPA is a critical instrument for global catastrophic risk, including two illustrative examples for how the DPA could be used for a major volcanic eruption or an AI-enabled cyberattack on energy grids.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, an international advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.